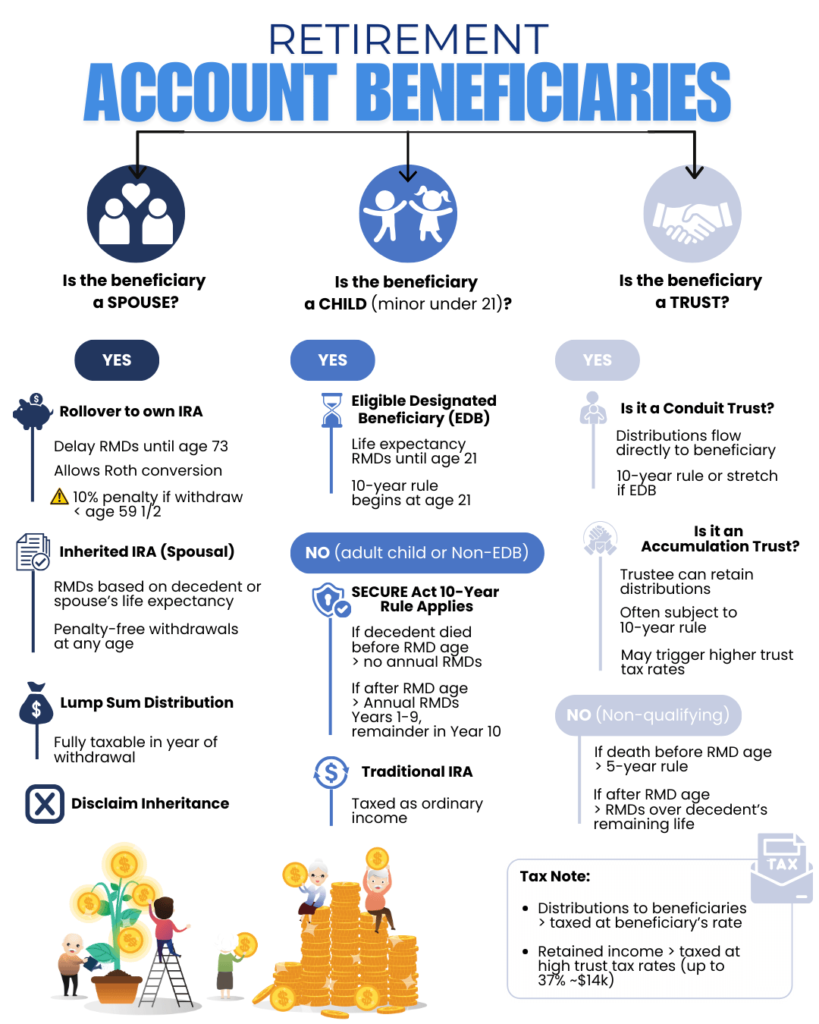

With the ever-changing legal landscape, a common client question is how to properly designate a beneficiary of an investment retirement account (e.g., 401(k)s, Roth IRAs, Traditional IRAs, etc.). Here we explore the options for spouses, children, and trusts (including conduit versus accumulation trusts), to inherit these accounts and the specific rules, income tax effects, and the pros and cons of certain designations.

How a Spouse Can Inherit an IRA

A surviving spouse named as the beneficiary of an IRA enjoys unique flexibility not afforded to other heirs. The options include rolling the IRA into their own account, maintaining it as an inherited IRA, converting it to a Roth IRA, taking a lump-sum distribution, or disclaiming the inheritance.

Rollover to Own IRA: A spouse can roll the inherited IRA into their own IRA, treating it as their IRA. This allows the spouse to delay required minimum distributions (RMDs) until the spouse attains age 73 (under current SECURE 2.0 rules) and name new beneficiaries. For example, a 60-year-old widow inheriting her 75-year-old husband’s IRA can roll it over and defer RMDs for 13 years, maximizing tax-deferred growth.

Withdrawals are taxed as ordinary income for traditional IRAs or tax-free for qualified Roth IRAs. However, if the spouse is under 59.5 years old, distributions before that age incur a 10% penalty, as the account loses its inherited status.

Remain as Inherited IRA: Alternatively, the spouse can keep the IRA as an inherited account. If the decedent spouse died before his or her RMD age, the spouse can delay RMDs until the decedent would have turned 73; at which time the RMDs would begin based on the spouse’s life expectancy.

A key advantage is penalty-free withdrawals at any age – a boon for a spouse under 59.5 years old needing funds. For instance, a 58-year-old inheriting a $500,000 IRA could access it without penalty, unlike a rollover scenario.

Roth Conversion: After rolling it into their own IRA, a spouse can convert a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA, paying taxes upfront but eliminating future RMDs and ensuring tax-free withdrawals.

This suits those expecting higher future tax rates or aiming to leave income tax-free assets to heirs.

Lump-Sum Distribution: A spouse can withdraw the entire account immediately. For a traditional IRA, this is fully taxable as ordinary income, potentially pushing the spouse into a higher tax bracket, though no penalty applies regardless of age.

Disclaimer: A spouse can disclaim the IRA within nine months of death, passing it to contingent beneficiaries (e.g., children). This might reduce estate taxes if the spouse’s estate is large or shift tax burdens to heirs in lower brackets.

How Children Can Inherit an IRA

Children inheriting an IRA – whether minors or adults – face stricter rules under the SECURE Act, with options varying by age and status as “eligible designated beneficiaries” (EDBs).

Minor children of the decedent (excluding grandchildren) each qualify as an EDB until age 21. They can stretch distributions over their life expectancy until reaching age 21, then must empty the account within 10 years of turning 21. For example, a 10-year-old inheriting a $300,000 IRA could take small annual RMDs (e.g., ~2% initially) until 21, then have until age 31 to withdraw the remainder.

If the decedent died after RMDs began, annual RMDs apply even during the stretch period.

Adult children, as non-EDBs, fall under the 10-year rule: the IRA must be fully distributed by December 31 of the tenth year after the decedent’s death. If the decedent died before RMDs, no annual distributions are required within that period; if after, annual RMDs based on the child’s life expectancy apply in years one through nine, with the remainder due in year 10. For instance, a 50-year-old inheriting a $300,000 IRA from a 75-year-old parent must take annual RMDs and empty it by year 10.

Tax Implications: Distributions from traditional IRAs are taxed as ordinary income at the child’s rate.

How a Trust Can Be the Beneficiary of an IRA

Naming a trust as an IRA beneficiary may allow control over distributions, offering asset protection and divorce protections depending on the type of trust. By naming a trust rather than a surviving spouse as a beneficiary of an IRA offers the advantage of allowing the spouse to benefit from the RMDs but also locks in the residuary beneficiaries of the IRA after the surviving spouse’s death (e.g., as the surviving spouse does not own the IRA, the surviving spouse cannot name a new spouse as the beneficiary after the surviving spouse’s death).

Trusts can be “see-through” (designated beneficiaries) or non-qualifying, with see-through trusts further divided into conduit and accumulation types:

A see-through trust meets IRS criteria (i.e., a valid irrevocable trust with identifiable beneficiaries) and uses the beneficiaries’ status to determine RMDs. A trust for a minor child could stretch distributions until 21, then switch to the 10-year rule; a trust with non-EDBs follows the 10-year rule outright.

- In a see-through conduit trust, all IRA distributions must pass immediately to the beneficiary. Only the primary beneficiary’s status (e.g., EDB or non-EDB) dictates RMDs, simplifying calculations. For example, a conduit trust for a spouse could stretch over her life expectancy, ignoring remainder beneficiaries.

- A see-through accumulation trust allows the trustee to retain IRA distributions, distributing them later at their discretion. All potential beneficiaries affect RMDs, often resulting in the 10-year rule unless all are EDBs. This offers greater control and protection but complicates planning.

Non-Qualifying Trust: If a trust fails see-through criteria (e.g., includes a charity), it follows the five-year rule (pre-RMD death) or the decedent’s remaining life expectancy (post-RMD death), accelerating payouts.

Conduit vs. Accumulation Trust

Conduit Trust Mechanics: All IRA withdrawals must flow to the beneficiary annually (i.e., for purposes of the RMD, the trust is disregarded).

For example, a conduit trust for a 30-year-old non-EDB would distribute the IRA over 10 years, with the final amount paid out in year 10. Whereas a conduit trust for a surviving spouse would be treated as an inherited IRA, with RMDs spread based on the spouse’s life expectancy.

Accumulation Trust Mechanics: The trustee has the discretion to hold distributions within the trust (i.e., the trust is not disregarded for purposes of the RMDs).

For the same 30-year-old, the IRA must be emptied by year 10, but the trustee could retain the funds, distributing them later based on trust terms. This treatment would also apply for an accumulation trust, whereby the surviving spouse is the beneficiary.

Tax Differences: Conduit trust distributions are taxed at the beneficiary’s rate, while retained accumulation trust RMDs face trust tax rates (37% federal on income over ~$14,000 in 2025), if the accumulation trust does not distribute the RMD to the beneficiary.

Income Tax Effects

Traditional Accounts: Withdrawals from traditional IRAs or 401(k)s are taxed as ordinary income. A spouse rolling over an IRA pays tax on distributions at their rate; a child under the 10-year rule faces tax based on withdrawal timing. Trusts retaining funds pay higher trust rates, while passing them out shifts the tax to the beneficiary.

Roth Accounts: Roth distributions are tax-free if the account is at least five years old, incentivizing beneficiaries to delay withdrawals within allowed periods for maximum growth.

Spousal Strategies: A spouse converting to a Roth pays tax upfront, potentially at a lower rate, benefiting heirs with tax-free funds.

How the 10-Year Rule Works

The SECURE Act’s 10-year rule applies to most non-EDB beneficiaries (e.g., adult children, most trusts) for deaths after 2019. The account must be fully distributed by the tenth year following the decedent’s death. If the decedent died before RMDs, beneficiaries can choose their withdrawal schedule; if after, annual RMDs apply in years 1-9, with the rest due in year 10. For example, a 50-year-old inheriting from a post-RMD parent must take annual RMDs and empty the account by year 10, while a pre-RMD death allows flexibility until the deadline.

Pros and Cons of Each Option

Spousal Rollover:

- Pros: Delays RMDs to age 73, allows new beneficiary designations, and supports Roth conversions for tax-free growth.

- Cons: Withdrawals before 59.5 years old incur a 10% penalty, limiting early access. The surviving spouse may change who the beneficiary of the IRA is after the surviving spouse’s death (e.g., the surviving spouse may name a subsequent spouse as the new beneficiary).

Spousal Inherited IRA:

- Pros: Penalty-free withdrawals at any age and delayed RMDs if the decedent was younger.

- Cons: No new contributions or rollovers, and RMDs are mandatory once started (unless using the SECURE 2.0 spouse election). The surviving spouse may change who the beneficiary of the IRA is after the surviving spouse’s death (e.g., the surviving spouse may name a subsequent spouse as the new beneficiary).

Spousal Disclaimer:

- Pros: Shifts assets to heirs, potentially reducing estate taxes or aligning with planning goals.

- Cons: Spouse loses control and heirs face the 10-year rule. In addition, the disclaimer must adhere to stringent rules to be legally effective.

Minor Child (Direct):

- Pros: Stretches distributions until 21, with small RMDs preserving growth.

- Cons: Full control at 21 risks mismanagement and the 10-year rule applies post age 21.

Adult Child (Direct):

- Pros: Flexibility within 10 years to manage taxes, no trust costs.

- Cons: No creditor or divorce protections with respect to RMDs and the remainder beneficiary may be changed by the adult child.

Conduit Trust:

- Pros: Ensures distributions to the beneficiary with simpler RMD rules and some protection while in the IRA.

- Cons: Funds paid out creditor and divorce protection, and the beneficiary may re-direct who receives the funds upon their death.

Accumulation Trust:

- Pros: Maximizes control and creditor protection, ideal for spendthrifts or special needs beneficiaries and prevents beneficiaries from changing who receives the IRA upon their death (e.g., a surviving spouse cannot leave the IRA to a new spouse).

- Cons: Potentially higher trust taxes on retained funds, complex administration, and often the 10-year rule.

Conclusion

The optimal inheritance structure for retirement accounts hinges on the client’s priorities – whether tax deferral, asset protection, or control. Spouses benefit from rollovers or inherited IRAs, children navigate the 10-year rule (with minors stretching until 21), and trusts offer tailored solutions at a tax cost. Consulting with your financial advisor, accountant, and estate planning attorney is essential to align the various options with your tax and non-tax goals.

This blog was drafted by Samuel M. DiPietro, an attorney in the Spencer Fane Phoenix, Arizona, office. For more information, visit www.spencerfane.com

Click here to subscribe to Spencer Fane communications to ensure you receive timely updates like this directly in your inbox.